APA 7: TWs Editor. (2023, November 15). Contemporary Earthquakes Could Stem from 1800s Seismic Activity: A Possible Aftershock Connection. PerEXP Teamworks. [News Link]

Following an earthquake, there is a phenomenon known as aftershocks, which are smaller quakes that persist in shaking the area for varying durations, ranging from days to years after the initial seismic event. These aftershocks gradually diminish over time and are integral to the fault’s re-adjustment process subsequent to the primary earthquake. Despite being of smaller magnitude compared to the main shock, these aftershocks possess the potential to cause infrastructure damage and hinder the recovery efforts initiated after the original earthquake.

Yuxuan Chen, a geoscientist at Wuhan University and the lead author of the study, highlighted a scientific discourse regarding seismic activity in certain stable regions of North America. While some scientists theorize that this seismicity represents aftershocks, others contend that it predominantly constitutes background seismic activity. Chen explained that the study aimed to provide a fresh perspective on this matter by employing a statistical method for analysis.

Areas in close proximity to the epicenters of historic earthquakes continue to exhibit seismic activity today, raising the possibility that certain contemporary earthquakes might be prolonged aftershocks from earlier seismic events. Alternatively, these earthquakes could be considered foreshocks, indicating the potential for larger seismic events in the future. Additionally, they might be attributed to background seismicity, representing the usual level of seismic activity expected in a given region.

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) emphasizes the challenge of distinguishing foreshocks from background seismicity until a larger earthquake occurs. However, scientists have the capability to identify aftershocks. Therefore, understanding the cause of contemporary earthquakes is crucial for assessing the future disaster risk in these regions, even if the present seismic activity is causing minimal to no damage.

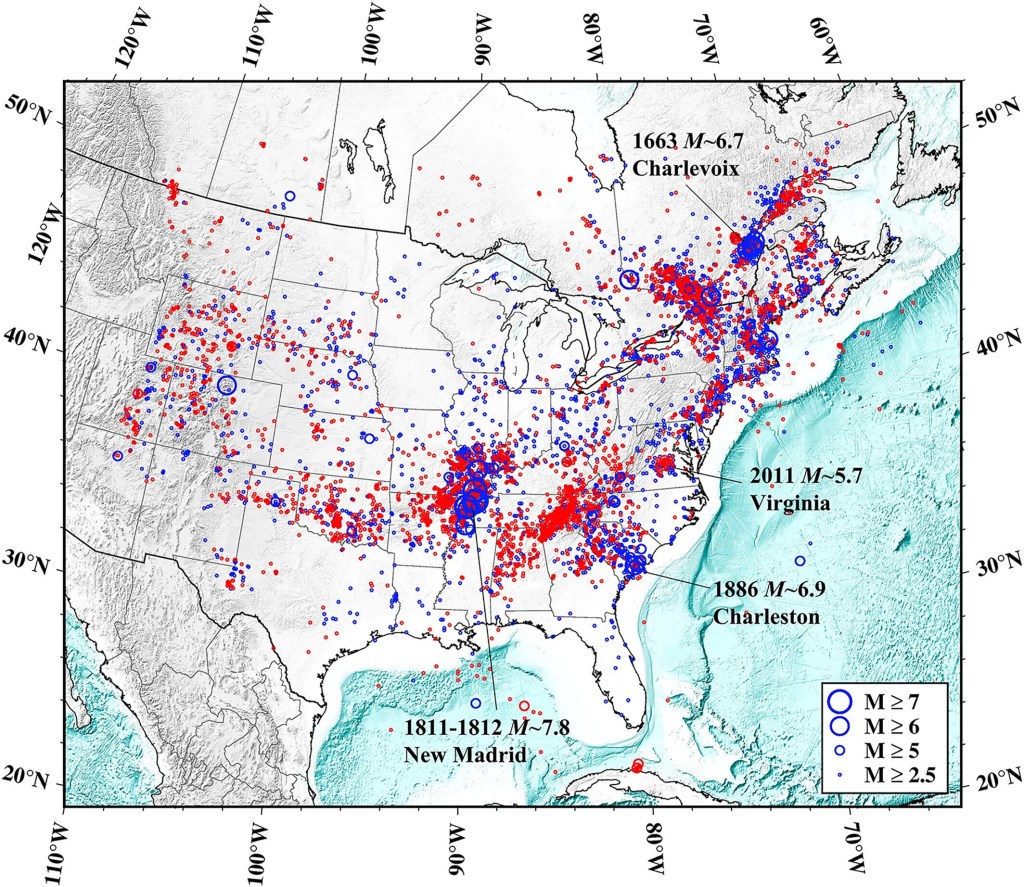

Concentrating on three significant earthquake occurrences with estimated magnitudes ranging from 6.5 to 8.0, the team examined seismic events in stable North America. These included an earthquake near southeastern Quebec, Canada, in 1663, a series of three quakes near the Missouri-Kentucky border from 1811 to 1812, and an earthquake in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1886. Notably, these three events stand as the most substantial earthquakes in the recent history of stable North America, and larger seismic events typically lead to a higher frequency of aftershocks.

Situated at a considerable distance from plate boundaries, the stable continental interior of North America experiences notably less tectonic activity compared to regions proximate to plate boundaries, such as the west coast. This low level of seismic activity in the three study areas raises additional inquiries about the underlying causes of their modern seismicity.

In their quest to ascertain if certain contemporary earthquakes are enduring aftershocks, the team initiated the process by identifying the specific modern seismic events to concentrate on. Given that aftershocks tend to cluster around the original earthquake’s epicenter, the team considered earthquakes falling within a 250-kilometer (155-mile) radius of the historical epicenters. They specifically concentrated on earthquakes with a magnitude greater than or equal to 2.5, as recording seismic events smaller than this threshold presents challenges in terms of reliability.

Utilizing the nearest neighbor method on earthquake data from the USGS, the team employed a statistical approach to discern whether recent seismic events were probable aftershocks or independent background seismic activity. According to the USGS, aftershocks typically manifest in close proximity to the original quake’s epicenter and precede the return to normal levels of background seismicity. Consequently, scientists can establish a connection between an earthquake and its mainshock by considering the region’s background seismicity and the location of the seismic event.

Chen explained the methodology, which involves considering the time, distance, and magnitude of pairs of seismic events. The objective is to establish a link between two events. If the distance between a pair of earthquakes is closer than what would be anticipated based on background events, it suggests that one earthquake is likely the aftershock of the other.

Susan Hough, a geophysicist affiliated with the USGS and not associated with the study, notes that the proximity between epicenters constitutes just one element of the overall puzzle.

According to Hough, when examining the spatial distribution, the earthquakes share characteristics with aftershocks. However, she emphasizes that tightly clustered earthquakes could have multiple explanations. While one possibility is that they are indeed aftershocks, another explanation could involve a process of creep that is unrelated to an aftershock sequence. The interpretation of the study’s results remains open to question and further investigation.

Upon analyzing the spatial distribution, the study determined that the aftershock sequence from 1663 near southeastern Quebec, Canada, has concluded, and the contemporary seismic activity in the area is not connected to the historical quake. In contrast, the study suggests that the other two historical events might still be inducing aftershocks centuries after their occurrence.

In the vicinity of the Missouri-Kentucky border, the investigation revealed that approximately 30% of all earthquakes recorded between 1980 and 2016 were probable aftershocks stemming from the major earthquakes that occurred in the region between 1811 and 1812. Similarly, in Charleston, South Carolina, the team identified that roughly 16% of contemporary seismic events were likely aftershocks originating from the earthquake in 1886. Consequently, the study suggests that the modern seismic activity in these regions is likely a result of a combination of aftershocks and background seismicity. Chen described it as a blend or combination of factors.

In evaluating a region’s contemporary seismic risk, scientists consider not only aftershocks but also monitor creep and background seismicity. The study indicates that background seismicity emerges as the primary contributor to earthquakes in all three study regions, suggesting ongoing strain accrual. While aftershock sequences tend to diminish over time, the accumulation of strain can potentially result in more substantial earthquakes in the future. It’s important to note that certain faults can experience creep without accumulating strain.

Hough emphasized the significance of comprehending seismic events that occurred 150 or 200 years ago in order to formulate a hazard assessment for the future. Employing modern methods in addressing this historical data becomes crucial in enhancing our understanding of seismic risks.

Resources

- NEWSPAPER American Geophysical Union. (2023, November 14). Some of today’s earthquakes may be aftershocks from quakes in the 1800s. Phys.org. [Phys.org]

- JOURNAL Chen, Y., & Liu, M. (2023). Long‐Lived Aftershocks in the New Madrid seismic Zone and the Rest of Stable North America. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 128(11). [Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth]