In the real world, laws are frequently violated. Alongside common criminals, there are scammers and fraudsters, politicians and mobsters, corporations and nations that treat laws as mere suggestions rather than firm restrictions. This is not the case in the realm of physics.

For centuries, physicists have been discovering laws of nature that are unbreakable. These laws govern matter, motion, electricity, gravity, and almost every other known physical process. They are the foundation of everything from the weather to nuclear weaponry. Most of these laws are well understood, at least by the experts who study and apply them. However, one law remains enigmatic.

This law is widely recognized as unbreakable and universally applicable. It influences the functioning of machines, life, and the universe as a whole. Despite its significance, scientists have not agreed on a single, clear way of expressing it, and its fundamental basis remains unexplained — rigorous attempts to prove it have been unsuccessful. This law is known as the second law of thermodynamics, often referred to simply as the Second Law.

In simplified terms, the Second Law states that heat flows from hot to cold, doing work always generates waste heat, and order tends to give way to disorder. However, its technical definition is complex and has eluded precise phrasing despite numerous efforts. As noted by a 20th-century physicist, there have been nearly as many formulations of the second law as there have been discussions about it. This highlights the challenges scientists face in definitively capturing the essence of this fundamental principle of thermodynamics.

This month marks the 200th anniversary of the Second Law of thermodynamics. It originated from the work of French engineer Sadi Carnot, who was trying to understand the physics of steam engines. Over time, this law became the foundation for comprehending the role of heat in all natural processes. However, its importance was not immediately recognized. It took two decades before physicists began to grasp the significance of Carnot’s findings.

By the early 20th century, the Second Law had gained prominence and was considered by some to be the most important law in physical science. British astrophysicist Arthur Stanley Eddington emphasized its supreme importance by stating that any theory conflicting with the second law of thermodynamics was doomed to fail and would result in profound embarrassment for its proponents.

Throughout its 200-year history, the Second Law has been instrumental in both technological advancements and fundamental scientific understanding. It underpins everyday phenomena such as the cooling of coffee, the operation of air conditioning and heating systems, and the mechanics of energy production in power plants and consumption in cars. It is crucial for understanding chemical reactions and even predicts the ultimate fate of the universe, known as the “heat death,” where all energy will eventually be uniformly distributed, leading to a state of no thermodynamic free energy to perform work. Additionally, the Second Law helps explain why time seems to flow in one direction.

Initially, the focus was on improving steam engines, but the implications of the Second Law of thermodynamics have since extended far beyond its origins, influencing a vast array of scientific and engineering disciplines.

Origins of the Second law of thermodynamics

“Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot was born in 1796 to Lazare Carnot, a prominent French engineer and government official. During a tumultuous period in France, Lazare found himself out of favor politically and went into exile in Switzerland and later Germany, while Sadi’s mother took him to a small town in northern France. Eventually, political power shifted, allowing Lazare to return to France, aided by his previous connection with Napoleon Bonaparte. Notably, Napoleon’s wife once babysat young Sadi.

According to a biography by his younger brother Hippolyte, Sadi was of delicate health but counteracted this with vigorous exercise. He was energetic yet somewhat of a loner, often reserved to the point of seeming rude. Despite this, from an early age, he displayed a profound intellectual curiosity that blossomed into undeniable genius.

By the age of 16, Sadi began his higher education in Paris at the prestigious École Polytechnique, having already received thorough training in mathematics, physics, and languages from his father. His further studies included mechanics, chemistry, and military engineering. During this period, he started writing scientific papers, although none have survived.

After serving as a military engineer, Carnot returned to Paris in 1819 to pursue his scientific interests. He took additional college courses, including one on steam engines, which deepened his longstanding fascination with industrial and engineering processes. He soon began writing a treatise on the physics of heat engines, where he first identified the scientific principles behind the production of useful energy from heat. Published on June 12, 1824, Carnot’s “Reflections on the Motive Power of Heat” provided the world with its initial insight into the second law of thermodynamics.

Computer scientist Stephen Wolfram recently highlighted that Carnot successfully demonstrated the theoretical maximum efficiency for a heat engine, which depends solely on the temperatures of its hot and cold heat reservoirs. In establishing this, Carnot effectively introduced the Second Law of thermodynamics.

Carnot’s study of steam engines, particularly their use in 18th century England and their pivotal role in driving the Industrial Revolution, was crucial. Steam engines had become indispensable to society, powering industries and commerce. Carnot recognized their transformative impact, noting their applications in mining, shipping, port and river excavation, iron forging, wood shaping, grain grinding, and textile production.

However, despite the widespread use of steam engines, the physical principles behind their conversion of heat into work were poorly understood. Carnot observed that the theory of steam engines was rudimentary and that improvements were often made by chance rather than through scientific understanding. He believed that enhancing steam engines required a comprehensive understanding of heat, independent of the specific properties of steam. Thus, he explored the workings of all heat engines, regardless of the medium used to transfer heat.

At the time, heat was commonly thought to be a fluid substance called caloric, which flowed between bodies. Carnot adopted this view and analyzed the flow of caloric in an idealized engine comprising a cylinder and piston, a boiler, and a condenser. In this setup, water could be transformed into steam in the boiler, the steam could then expand in the cylinder to drive the piston and perform work, and finally, the steam could be condensed back into liquid water in the condenser.

Carnot’s key insight was that heat generates motion and performs work by moving from a higher temperature to a lower temperature (in steam engines, this means from the boiler to the condenser). He concluded that the production of motive power in steam engines is due to the transfer of heat, not its actual consumption.

This evaluation of the process, now known as the Carnot cycle, revealed the method for calculating the maximum efficiency achievable by any engine — essentially, the amount of work that can be produced from the heat. A significant implication of the Second Law of thermodynamics is that it is impossible to convert all the heat into work.

Although Carnot’s belief in caloric as a fluid substance was incorrect, his conclusions were accurate. Heat is actually the motion of molecules, but the Second Law holds true regardless of the substance used by an engine or the true nature of heat. This might be what Einstein was alluding to when he remarked that thermodynamics is likely to remain one of the most enduring scientific achievements, even as other advances reshape our understanding of the cosmos.

Einstein expressed confidence in thermodynamics, asserting that within the scope of its fundamental principles, it is the only physical theory of universal content that he believed would never be overturned.

The second law foresees universal heat death

Carnot’s book received some attention, including a positive review in the French periodical Revue Encyclopédique, but it was largely overlooked by the scientific community. Carnot did not publish any further works and died of cholera in 1832. However, in 1834, French engineer Émile Clapeyron summarized Carnot’s work in a paper that made it more accessible. About a decade later, British physicist William Thomson, later known as Lord Kelvin, encountered Clapeyron’s paper and validated that Carnot’s core conclusions remained valid, even after the caloric theory was replaced by the understanding that heat is the motion of molecules.

Around the same time, German physicist Rudolf Clausius articulated an early explicit statement of the Second Law of thermodynamics, noting that an isolated machine cannot transfer heat from a cooler body to a warmer one without external input. Independently, Kelvin reached a similar conclusion, stating that no material could do work by cooling itself below the temperature of the coldest surrounding objects. These statements were essentially equivalent and formed complementary expressions of the Second Law.

The term Second Law emerged because the conservation of energy, or the first law of thermodynamics, had already been established. The first law states that the total energy in any physical process remains constant, meaning energy can neither be created nor destroyed. However, the Second Law is more intricate. While the total energy remains unchanged, not all of it can be converted into work. Some energy inevitably dissipates as waste heat, which cannot be used to perform further work.

Kelvin noted that when heat transfers from a warmer body to a cooler one, there is an unavoidable waste of mechanical energy available for human use. This dissipation of energy into waste heat indicated a grim outlook for the universe. Building on Kelvin’s insight, German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz later pointed out that eventually, all useful energy would become unusable. At that point, everything in the universe would reach the same temperature. Without temperature differences, no work could be done, and all natural processes would stop. Von Helmholtz described this scenario as the universe being condemned to a state of eternal rest. Fortunately, this “heat death of the universe” is not expected to occur for eons.

In the meantime, Clausius introduced the concept of entropy to quantify the conversion of useful energy into useless waste heat, offering another way to express the Second Law of thermodynamics. Clausius summarized the first law of thermodynamics as “the energy of the universe is constant” and proposed that the Second Law could be summarized as “the entropy of the universe tends to a maximum.”

Entropy can be understood as a measure of disorder. An orderly system, left on its own, will naturally become disordered. More technically, the temperature differences within a system will equalize until the system reaches a uniform temperature, achieving equilibrium.

From another perspective, entropy is related to the probability of a system’s state. A system with low entropy is highly ordered and exists in a state of low probability because there are many more ways for the system to be disordered than ordered. High-entropy, disordered states are much more likely. Consequently, entropy tends to increase or at least remain constant in systems where molecular motion has reached equilibrium.

Introducing probability into the discussion suggested that proving the Second Law of thermodynamics through the analysis of individual molecular motions would be impossible. Instead, it required the study of statistical measures describing the behavior of large numbers of molecules. Physicists like James Clerk Maxwell, Ludwig Boltzmann, and J. Willard Gibbs developed statistical mechanics, which uses mathematics to describe the large-scale properties of matter based on the statistical interactions of its molecules.

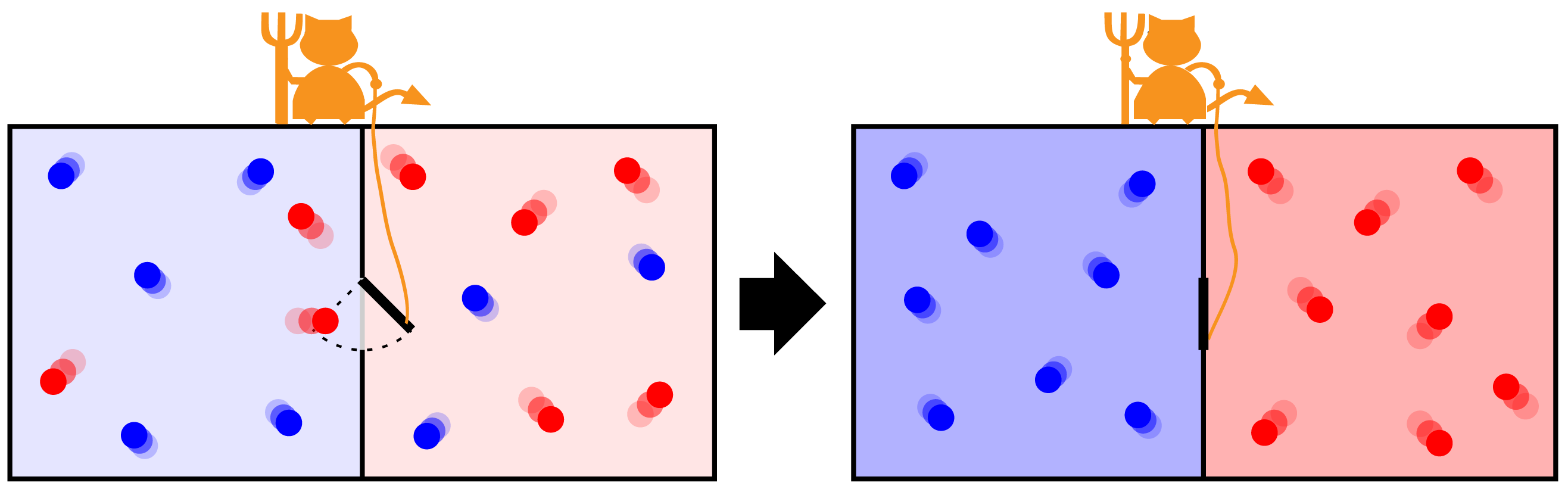

Maxwell determined that the Second Law holds statistical validity, meaning it describes the most probable processes. This implies that while it’s not impossible, it’s highly unlikely for heat to flow from cold to hot. To illustrate, Maxwell conceived a hypothetical being (later called a “demon” by Kelvin) that could control a tiny door between two gas chambers. By selectively allowing only slow molecules to pass in one direction and fast molecules in the other, the demon could theoretically make one chamber hotter and the other colder, thereby violating the Second Law.

However, in the 1960s, IBM physicist Rolf Landauer demonstrated that erasing information inevitably produces waste heat. His colleague Charles Bennett later pointed out that a Maxwell demon would need to record molecular velocities to determine when to open and close the door. Without infinite memory, the demon would eventually need to erase these records, thus generating waste heat and ultimately preserving the Second Law of thermodynamics.

Another intriguing aspect arising from the study of the Second Law is its relationship to the direction of time. The laws governing molecular motion apply equally to the past and the future — a reversal of a video showing molecular collisions would still adhere to these laws. Yet in reality, time always moves forward, unlike the reversible scenarios often depicted in science fiction.

One might infer that the Second Law, which mandates the increase of entropy, influences the direction of time’s arrow. However, the Second Law alone cannot explain why entropy in the universe hasn’t already peaked. Many contemporary scientists argue that the direction of time’s arrow cannot solely be attributed to the Second Law. They suggest it likely involves factors related to the universe’s origin and its expansion post-Big Bang. There seems to have been a low entropy state at the universe’s beginning, but the reasons behind this initial condition remain an enigma.

The Second Law Lacks Rigorous Proof

In his exploration of the history of the Second Law, Wolfram details numerous past attempts to establish a solid mathematical foundation for it, all of which have fallen short. He notes that by the late 1800s, there was a tendency to treat the Second Law as a necessary principle in physics, almost proven mathematically. However, Wolfram points out persistent weaknesses in the logical chain of mathematical reasoning. Despite widespread assumptions that the law had been fully validated, his survey reveals that this is not the case.

Recent efforts to substantiate the Second Law often invoke Landauer’s insights on information erasure, connecting the law to information theory. For instance, Shintaro Minagawa and colleagues propose that integrating the Second Law with information theory can strengthen its foundational basis, introducing the concept of the “second law of information thermodynamics” as universally applicable in physics.

Another perspective, endorsed by Wolfram, suggests that the Second Law finds validation through principles governing computation. He argues that its essence lies in the ability of simple computational rules to produce complex outcomes, a concept termed computational irreducibility.

Despite ongoing efforts by researchers to validate or challenge the Second Law, the question of its universal truth remains unresolved. Some have attempted to refute its applicability, but according to a 2020 review in the journal Entropy by Milivoje M. Kostic, all challenges to the Second Law thus far have been resolved in favor of it. Kostic emphasizes that no conclusive violations of the Second Law have been substantiated, reinforcing its robustness within the framework of thermodynamics.

However, the universal validity of the Second Law of thermodynamics remains a subject of ongoing debate. Resolving this question may necessitate a clearer definition of the law itself. Variants of Clausius’ assertion that entropy tends to increase are commonly cited as definitions of the Second Law. Yet, physicist Richard Feynman found this formulation unsatisfactory and preferred a more operational definition: “A process that only results in taking heat from a reservoir and converting it entirely into work is impossible.”

When Carnot first articulated the Second Law, he described it without formally defining it, perhaps sensing that the concept required further refinement over time. He recognized early on that future advancements would illuminate the true nature of heat. In his unpublished writings, Carnot explored the equivalence between heat and mechanical motion, laying the groundwork for what would later become known as the first law of thermodynamics. He also anticipated the eventual debunking of the caloric theory, citing experimental evidence that challenged it. According to Carnot, heat was fundamentally a form of motion among particles within bodies.

Carnot intended to conduct experiments to test these revolutionary ideas, but his untimely death intervened, highlighting one of nature’s irrefutable certainties, alongside taxes. Some may ponder whether the Second Law itself qualifies as a third certainty.

Regardless of its inviolability, the enduring truth remains that human laws are far more susceptible to breach than the laws of nature.

- ONLINE NEWS Siegfried, T. (2024, June 12). The second law of thermodynamics underlies nearly everything. But is it inviolable? Science News. [Science News]

- JOURNAL Minagawa, S., Sakai, K., Kato, K., & Buscemi, F. (2023). Universal validity of the second law of information thermodynamics. arXiv (Cornell University). [arXiv.org]

- WEBSITE Wolfram, S. (2023, February 3). Computational Foundations for the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Stephen Wolfram Writings. [Stephen Wolfram Writings]

- WEBSITE Wolfram, S. (2023, January 31). How Did We Get Here? The Tangled History of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Stephen Wolfram Writings. [Stephen Wolfram Writings]

- JOURNAL Kostic, M. M. (2020). The second law and entropy misconceptions demystified. Entropy, 22(6), 648. [Entropy]

APA 7: TWs Editor. (2024, June 21). The Second Law of Thermodynamics: Unbreakable Physics?!. PerEXP Teamworks. [Online News Link]