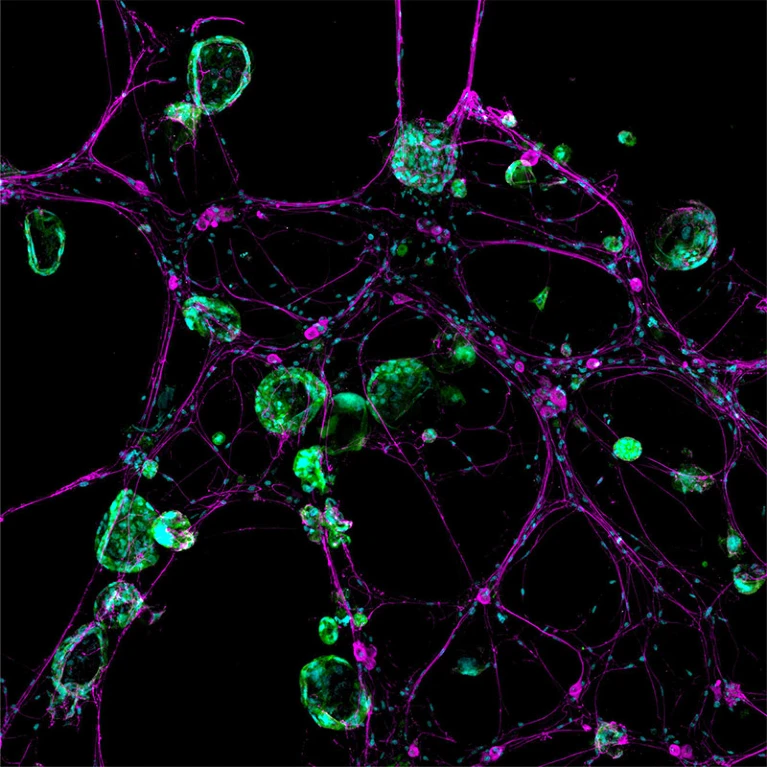

In the late months of 2017, amidst the dim glow of her computer screen, cancer neuroscientist Humsa Venkatesh was transfixed by a mesmerizing spectacle. Lime-green lightning bolts danced erratically, illuminating the chaotic storm of electrical activity within cells extracted from a human brain tumour known as a glioma.

Venkatesh had anticipated some level of background commotion among the cancerous brain cells, akin to the subtle exchanges among their healthy counterparts. However, what she witnessed exceeded all expectations. The cellular conversations unfolded with relentless intensity and rapid succession. “I could see these tumour cells just lighting up,” Venkatesh recalled, reflecting on her time as a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California. “They were so clearly electrically active.”

The implications immediately seized her thoughts. Until then, the scientific community had scarcely entertained the notion that cancer cells, particularly those nestled within the intricate folds of the brain, could engage in such extensive communication. Venkatesh pondered whether the tumour’s ceaseless electrical dialogues might play a pivotal role in its survival, or perhaps even in its relentless expansion. “This is cancer that we’re working on — not neurons, not any other cell type.” Witnessing the cells ablaze with such fervent activity was, in Venkatesh’s words, “truly mind-blowing.” She has since transitioned to Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

Venkatesh’s groundbreaking research contributed to a pivotal 2019 paper in Nature, alongside another seminal article that echoed the same revelation: gliomas possess a distinct electrical vitality. These tumours possess the remarkable ability to integrate themselves into neural networks, receiving direct stimulation from neurons—a phenomenon that fuels their growth and resilience.

The discoveries have proven to be groundbreaking in the burgeoning field of cancer neuroscience, where scientists delve into the multifaceted ways cancer—whether within or outside the brain—harnesses the nervous system for its own advantage. Similar to how tumors enlist blood vessels to sustain themselves and proliferate, cancer strategically leverages the nervous system for various functions, ranging from initiation to metastasis.

The intersection of oncology and neuroscience is just beginning to unfold within this previously overlooked aspect of the tumor microenvironment. Researchers are gradually unraveling the intricacies of which neurons and signals participate in these processes, yet the newfound connections with the immune system further complicate the narrative. As scientists delve deeper into the complex interplay between cancer and the nervous system, novel therapies targeting these connections are emerging. Some of these therapeutic approaches repurpose existing drugs to enhance outcomes for individuals battling cancer.

Cancer biologist Erica Sloan, based at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, underscores the overarching mission of their research efforts. While acknowledging the intellectual intrigue inherent in unraveling the intricacies of biology, Sloan emphasizes the primary objective: to translate these insights into tangible benefits for patients. The focus lies not only on comprehending the underlying biological mechanisms but also on determining how to effectively apply this knowledge to improve patient outcomes.

Nerves and cancer interactions

Scientists initially observed connections between cancer cells and neurons nearly two centuries ago. In the mid-nineteenth century, French anatomist and pathologist Jean Cruveilhier documented a case where breast cancer infiltrated the cranial nerve responsible for facial movement and sensations.

This historical account marked the discovery of perineural invasion, a process where cancer cells intertwine with nerves, facilitating their spread. Perineural invasion often indicates an aggressive tumor and predicts unfavorable health outcomes.

For years, the prevailing belief among scientists and healthcare professionals was that nerves merely served as passive conduits for cancer and its associated pain. According to neuro-oncologist Michelle Monje at Stanford University School of Medicine, who served as Venkatesh’s advisor, the nervous system was perceived as “the victim—the structure that gets destroyed by or damaged by the cancer.”

However, in the late 1990s, urological pathologist Gustavo Ayala, currently at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, delved deeper into this interaction. He conducted experiments where mouse nerves were exposed to human prostate cancer cells in laboratory dishes. Remarkably, within 24 hours, the nerves sprouted small branches known as neurites, which extended toward the cancer cells. Upon contact, the cancer cells traversed along the nerves until they reached the neuronal cell bodies.

These findings unveiled the active role of nerves in seeking connections with cancer cells. Ayala was convinced of the significance of this discovery and dedicated his career to its exploration, earning him the moniker ‘the nerve guy’. Reflecting on his early pursuits in the field, Ayala recalls encountering skepticism from others who did not share his enthusiasm for the subject matter.

In 2008, Ayala unveiled another intriguing observation: prostate cancer tumors extracted from individuals who underwent surgery exhibited a higher density of nerve fibers, known as axons, compared to samples from healthy prostates.

While some scientists perceived this finding as unusual, others began to conceptualize tumors as complex organs in their own right. Tumors, they argued, possess diverse cell types, a supportive structural framework, blood vessels, and other components that set them apart from mere clusters of cancerous cells.

However, according to Claire Magnon, a cancer biologist at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research in Paris, there seemed to be a crucial missing piece in this conceptual landscape—nerves.

This intuition led to a pivotal discovery in 2013. Magnon and her research team documented the proliferation of nerve fibers within and surrounding prostate tumors in mice. Furthermore, disrupting the connections to the nervous system halted the progression of the disease. Within a few years, a surge of research confirmed similar phenomena in various other cancers, spanning from the stomach and pancreas to the skin. Some of these severed nerves were associated with cancer-related pain, and previous studies had demonstrated that blocking these pathways in individuals with pancreatic cancer could alleviate some symptoms.

Neuroscientist Brian Davis at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania remarks on the fortuitous alignment of circumstances. The accumulating evidence showcased “that this component of the tumor microenvironment, which had largely been overlooked, was indeed playing a significant role.”

Neural dynamics in tumorigenesis

However, the origins of these cancer-invading nerves puzzled researchers for some time. Investigations conducted in subsequent years hinted at the possibility that cells within the tumor could undergo a transformation into neurons, or at least adopt characteristics resembling those of neurons. Then, in 2019, Magnon and her research team unveiled yet another revelation. They observed neural progenitor cells migrating through the bloodstream to prostate tumors in mice, where they settled and matured into neurons. Astonishingly, cancers appeared to exert influence over the brain region housing these cells—the subventricular zone. In mice, these cells are recognized for aiding in the recovery from certain brain ailments, such as strokes. While some evidence suggests that this region also generates neurons in adult humans, this concept remains contentious.

In the subsequent year, another research group made a noteworthy discovery indicating that cancer can induce neurons to undergo a change in identity. Their study on oral cancer in mice revealed that sensory neurons—those responsible for transmitting sensations to the brain—acquired characteristics typical of a different type of neuron rarely found in the oral cavity: sympathetic neurons, which play a pivotal role in the ‘fight or flight’ response.

According to cancer neuroscientist Moran Amit at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, who co-led the study, cancer cells are now assuming dual roles. This transformation could potentially promote tumor growth, as sympathetic nerves have been demonstrated to be advantageous for certain cancers.

However, the interplay between nerve types and their impact on tumors is intricate. For instance, in the pancreas, there exists a dynamic interplay between two types of nerves with contrasting effects on tumors. Sympathetic nerves contribute to a detrimental feedforward loop that facilitates cancer growth. They emit signals prompting diseased cells to produce a protein known as nerve growth factor, which, in turn, attracts more nerve fibers. Conversely, their counterparts—parasympathetic nerves, responsible for the ‘rest and digest’ response—dispatch chemical messages that impede disease progression.

In stomach cancer, however, parasympathetic signals function oppositely, encouraging tumor expansion. Similarly, in prostate cancer, both nerve types assist tumors, with sympathetic nerves aiding in the early stages of cancer development and parasympathetic nerves facilitating later-stage spread.

Gastroenterologist Timothy Wang at Columbia University in New York City emphasizes that the interaction between cancer and the nervous system varies for each type of cancer. Consequently, treatment targets need to be tailored to the specific characteristics of the cancer and its utilization of the nervous system.

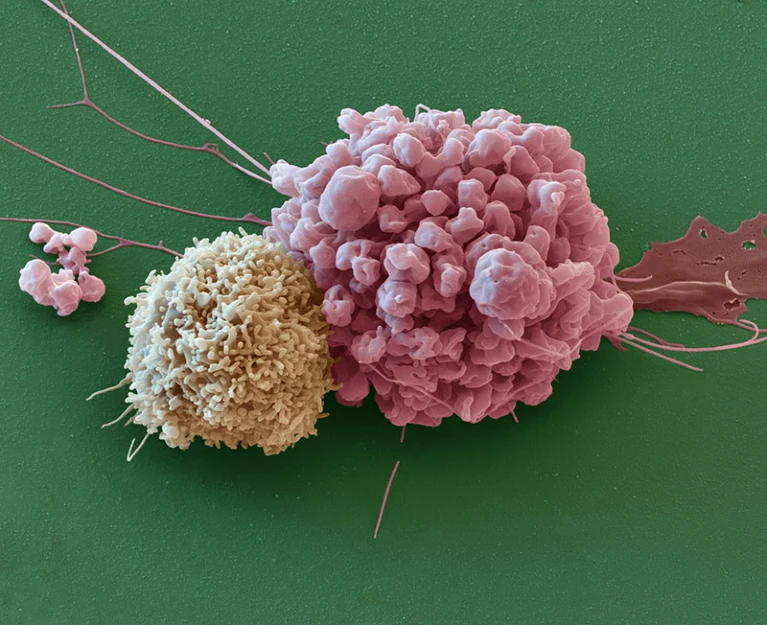

Neurons exert direct influences on cancers, while also engaging in indirect actions such as suppressing the immune system’s ability to combat tumors effectively. A recent discovery in 2022 points to one such mechanism: the release of a chemical known as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) by sensory nerves. CGRP has the ability to dampen the activity of specific immune cells, rendering them less equipped to fend off cancerous threats.

Neurons employ immune-cell suppression as a protective measure to safeguard themselves, as excessive inflammation can pose a threat to their integrity. According to cancer neuroscientist Jami Saloman at the University of Pittsburgh, nerves not only facilitate the spread of cancer by providing pathways and support structures but also serve as a sanctuary for cancer cells.

Neuroscientist Brian Davis elaborates that tumors can essentially nestle themselves within nerves, shielded from both the immune system and medication. This protection is due to the difficulty drugs face in penetrating nerves. Davis suggests that cancer cells can lie dormant within nerves, biding their time until the tumult of biologics and chemotherapy subsides. Subsequently, they can resurface and resume their malignancy.

Cancer’s intricate mimicry

Some of the most aggressive cancers have a profound impact on the brain. As Venkatesh and her colleagues discovered, cancer cells establish direct synaptic connections with neurons, leveraging their signals to promote growth.

A study published alongside the two brain cancer papers in 2019 revealed that metastases from breast cancer in the brain could also establish synapse-like connections. Previous research has also associated brain metastases with cognitive decline.

Brain cancers exhibit further similarities to brain cells in their behavior. Monje’s laboratory recently reported that gliomas reinforce their neuronal interactions using a well-known brain signaling mechanism. When exposed to brain-derived neurotrophic factor, a protein aiding neuronal growth, glioma cells respond by generating more receptors capable of receiving signals from neurons.

According to Monje, this mechanism mirrors the same process healthy neurons employ in learning and memory. She emphasizes that cancer doesn’t introduce novel mechanisms but rather co-opts existing processes for its own benefit.

Furthermore, akin to neural networks, certain glioma cells possess the ability to generate rhythmic waves of electrical activity. Frank Winkler, a neuro-oncologist at the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, describes them as resembling “little beating hearts,” drawing attention to their pulsating nature. His laboratory’s research delved into this phenomenon.

These electrical impulses propagate throughout the cancerous cells via a network of delicate, thread-like bridges known as tumor microtubes. Winkler’s team has been investigating these structures for several years. The orchestrated activity governs the proliferation and survival of cancer cells, mirroring the role of pacemaker neurons in coordinating neural circuit formation. Winkler highlights the alarming reality that cancer exploits crucial neural mechanisms of neurodevelopment.

Moreover, brain cancers can exert far-reaching effects on entire networks. A recent study revealed that gliomas have the capacity to reshape entire functional circuits within the brain. Individuals with tumors infiltrating speech-production areas were subjected to tasks involving naming items described in audio or depicted in pictures. Surface electrodes placed on their brains indicated that the language-related activity not only stimulated the expected language regions but also triggered heightened activity across the entire infiltrated area of the tumor, including regions typically not involved in speech production. The extent of functional connectivity between the tumor and the rest of the brain correlated with the individuals’ performance on the task and their projected survival duration.

Michelle Monje, who co-authored the study, reflects on her initial shock upon viewing the results. She emphasizes how the tumor had effectively rewired the functional language circuitry to sustain its own growth, underscoring the profound impact of such findings on understanding the complex dynamics of brain cancer.

Repurposing neurological drugs for cancer treatment

The initial discoveries in cancer neuroscience are already shedding light on potential treatments for cancer. They also provide insight into why current treatment options often result in adverse effects on the brain. According to Venkatesh, many individuals undergoing chemotherapy experience cognitive decline, commonly referred to as ‘chemo brain’, along with degeneration of nerve fibers throughout the body.

Destroying neurons elsewhere in the body through chemotherapy is evidently detrimental to patients, Venkatesh asserts.

One approach involves targeting specific aspects of the nervous system, utilizing existing therapies that possess well-established safety profiles. Amit highlights the potential of these therapies, noting that drugs targeting various branches of the nervous system are readily available.

For instance, beta blockers have shown promise in disrupting signals from sympathetic nerves that drive cancer progression in numerous organs, including the breast, pancreas, and prostate. Originally utilized to treat heart conditions like hypertension and anxiety since the 1960s, beta blockers are now being explored for their anticancer properties.

Sloan recounts facing skepticism when initially proposing to repurpose beta blockers for cancer treatment. However, her perseverance led to a phase II clinical trial published in 2020, which demonstrated that the beta blocker propranolol could reduce signs of cancer metastasis after just one week of treatment in individuals with breast cancer. Subsequent trials confirmed the safety of combining chemotherapy with propranolol, based on observational studies linking beta-blocker use to improved health outcomes. Additionally, Sloan’s research in the past year has shown that the drug enhances the effectiveness of common chemotherapy treatments.

Researchers are exploring the repurposing of drugs that disrupt neuronal communication, including medications initially developed for seizures and migraines. One clinical trial is underway, aiming to obstruct the synapses formed between neurons and cancer cells in gliomas by utilizing an anti-seizure drug. This medication functions to calm hyperexcitable cells within the brain.

In another trial in the planning stages, researchers intend to investigate whether individuals undergoing immunotherapy for skin or head-and-neck cancer could benefit from taking a migraine medication. The rationale behind this approach lies in the belief that migraines can be triggered by elevated levels of CGRP, a molecule capable of dampening the activity of certain immune cells in cancer. By blocking CGRP receptors, the migraine medication could counteract CGRP and potentially restore immune cells’ ability to combat cancer.

Humsa Venkatesh envisions that a combination of drugs with complementary effects will likely be necessary to manage the disease effectively. She emphasizes, “There is really no silver bullet.”

The field is still in its nascent stages of deciphering this complex relationship, leaving numerous unanswered questions. As Markus Winkler remarks, “I think I would need 50 lives to go after all of them.”

Resources

- JOURNAL Prillaman, M. (2024). How cancer hijacks the nervous system to grow and spread. Nature, 626, 22–24. [Nature]

- JOURNAL Venkatesh, H. S., Morishita, W., Geraghty, A. C., Silverbush, D., Gillespie, S., Arzt, M., Tam, L., Espenel, C., Ponnuswami, A., Ni, L., Woo, P., Taylor, K. R., Agarwal, A., Regev, A., Brang, D., Vogel, H., Hervey-Jumper, S., Bergles, D. E., Suvà, M. L., . . . Monje, M. (2019). Electrical and synaptic integration of glioma into neural circuits. Nature, 573(7775), 539–545. [Nature]

- JOURNAL Venkataramani, V., Tanev, D. I., Strahle, C., Studier-Fischer, A., Fankhauser, L., Keßler, T., Körber, C., Kardorff, M., Ratliff, M., Xie, R., Horstmann, H., Messer, M., Paik, S. P., Knabbe, J., Sahm, F., Kurz, F. T., Açıkgöz, A. A., Herrmannsdörfer, F., Agarwal, A., . . . Kuner, T. (2019). Glutamatergic synaptic input to glioma cells drives brain tumour progression. Nature, 573(7775), 532–538. [Nature]

- JOURNAL Ayala, G., Wheeler, T. M., Shine, H. D., Schmelz, M., Frolov, A., Chakraborty, S., & Rowley, D. R. (2001). In vitro dorsal root ganglia and human prostate cell line interaction: Redefining perineural invasion in prostate cancer. The Prostate, 49(3), 213–223. [The Prostate]

- JOURNAL Ayala, G., Dai, H., Powell, M., Li, R., Ding, Y., Wheeler, T. M., Shine, D. H., Kadmon, D., Thompson, T., Miles, B. J., Ittmann, M., & Rowley, D. R. (2008). Cancer-Related axonogenesis and neurogenesis in prostate cancer. Clinical Cancer Research, 14(23), 7593–7603. [Clinical Cancer Research]

- JOURNAL Magnon, C., Hall, S., Lin, J., Xue, X., Gerber, L., Freedland, S. J., & Frenette, P. S. (2013). Autonomic nerve development contributes to prostate cancer progression. Science, 341(6142). [Science]

- JOURNAL Mauffrey, P., Tchitchek, N., Barroca, V., Bemelmans, A., Firlej, V., Allory, Y., Roméo, P., & Magnon, C. (2019). Progenitors from the central nervous system drive neurogenesis in cancer. Nature, 569(7758), 672–678. [Nature]

- JOURNAL Amit, M., Takahashi, H., Dragomir, M. P., Lindemann, A., Gleber‐Netto, F. O., Pickering, C. R., Anfossi, S., Osman, A. A., Cai, Y., Wang, R., Knutsen, E., Shimizu, M., Ivan, C., Rao, X., Wang, J., Silverman, D. A., Tam, S., Zhao, M., Caulín, C., . . . Myers, J. N. (2020). Loss of p53 drives neuron reprogramming in head and neck cancer. Nature, 578(7795), 449–454. [Nature]

- JOURNAL Balood, M., Ahmadi, M., Eichwald, T., Ahmadi, A., Majdoubi, A., Roversi, K., Roversi, K., Lucido, C. T., Restaino, A., Huang, S., Ji, L., Huang, K., Semerena, E., Thomas, S. C., Trevino, A. E., Merrison, H., Parrin, A., Doyle, B., Vermeer, D. W., . . . Talbot, S. (2022). Nociceptor neurons affect cancer immunosurveillance. Nature, 611(7935), 405–412. [Nature]

- JOURNAL Zeng, Q., Michael, I. P., Zhang, P., Saghafinia, S., Knott, G., Jiao, W., McCabe, B. D., Galván, J. A., Robinson, H. P. C., Zlobec, I., Ciriello, G., & Hanahan, D. (2019). Synaptic proximity enables NMDAR signalling to promote brain metastasis. Nature, 573(7775), 526–531. [Nature]

- JOURNAL Taylor, K. R., Barron, T., Hui, A., Spitzer, A., Yalçın, B., Ivec, A. E., Geraghty, A. C., Hartmann, G. C., Arzt, M., Gillespie, S., Kim, Y. S., Jahan, S. M., Zhang, H., Shamardani, K., Su, M., Ni, L., Du, P., Woo, P., Silva-Torres, A., . . . Monje, M. (2023). Glioma synapses recruit mechanisms of adaptive plasticity. Nature, 623(7986), 366–374. [Nature]

- JOURNAL Hausmann, D., Hoffmann, D. C., Venkataramani, V., Jung, E., Horschitz, S., Tetzlaff, S., Jabali, A., Lü, H., Keßler, T., Azorín, D., Weil, S., Kourtesakis, A., Sievers, P., Habel, A., Breckwoldt, M. O., Karreman, M. A., Ratliff, M., Messmer, J. M., Yang, Y., . . . Winkler, F. (2022). Autonomous rhythmic activity in glioma networks drives brain tumour growth. Nature, 613(7942), 179–186. [Nature]

- JOURNAL Krishna, S., Choudhury, A., Keough, M. B., Seo, K., Ni, L., Kakaizada, S., Lee, A., Aabedi, A., Schmunk, G., Lipkin, B., Cao, C. G. L., Gonzales, C. N., Sudharshan, R., Egladyous, A., Almeida, N., Zhang, Y., Molinaro, A. M., Venkatesh, H. S., Daniel, A., . . . Hervey-Jumper, S. L. (2023). Glioblastoma remodelling of human neural circuits decreases survival. Nature, 617(7961), 599–607. [Nature]

- JOURNAL Hiller, J. G., Cole, S. W., Crone, E. M., Byrne, D., Shackleford, D. M., Pang, J., Henderson, M. A., Nightingale, S., Ho, K. M., Myles, P. S., Fox, S. B., Riedel, B., & Sloan, E. K. (2020). Preoperative β-Blockade with Propranolol Reduces Biomarkers of Metastasis in Breast Cancer: A Phase II Randomized Trial. Clinical Cancer Research, 26(8), 1803–1811. [Clinical Cancer Research]

- JOURNAL Hopson, M., Lee, J., Accordino, M. K., Trivedi, M. S., Maurer, M., Crew, K. D., Hershman, D. L., & Kalinsky, K. (2021). Phase II study of propranolol feasibility with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 188(2), 427–432. [Breast Cancer Research and Treatment]

- JOURNAL Chang, A., Botteri, E., Gillis, R. D., Løfling, L., Le, C. P., Ziegler, A. I., Chung, N., Rowe, M. C., Fabb, S. A., Hartley, B. J., Nowell, C. J., Kurozumi, S., Gandini, S., Munzone, E., Montagna, E., Eikelis, N., Phillips, S., Honda, C., Masuda, K., . . . Sloan, E. K. (2023). Beta-blockade enhances anthracycline control of metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer. Science Translational Medicine, 15(693). [Science Translational Medicine]

Cite this page:

APA 7: TWs Editor. (2024, February 4). Cancer Research: Uncovering Glioma Cells’ Shining Activity. PerEXP Teamworks. [News Link]