APA 7: TWs Editor & ChatGPT. (2023, October 6). Prokaryotic Cell. PerEXP Teamworks. [Article Link]

In the grand tapestry of life, prokaryotic cells stand as the earliest and most primitive threads. This article embarks on a journey through the microscopic world, exploring the profound simplicity of prokaryotic cells. From their defining characteristics to their intricate structure, components, modes of reproduction, and the remarkable examples that populate our planet, this narrative unveils the essence of these fundamental building blocks of life.

What is a prokaryotic cell?

Prokaryotic cells represent a foundational and evolutionarily ancient category of biological cells, characterized by their fundamental simplicity and lack of distinct membrane-bound organelles, including a nucleus. These microscopic entities, typically found in bacteria and archaea, consist of a singular, circular DNA molecule that resides in the cell’s nucleoid region, unenclosed by a membrane. Surrounding this genetic material is a cytoplasmic matrix, devoid of the compartmentalization seen in eukaryotic cells. Prokaryotic cells also exhibit a robust cell wall, essential for structural integrity and protection, and may possess additional structures like pili and flagella for mobility and adhesion. While prokaryotes lack the sophisticated internal compartments seen in eukaryotes, they are highly adaptable and have thrived in a myriad of ecological niches, playing vital roles in diverse ecosystems and even contributing to human health and industry.

Characteristics of prokaryotic cell

Prokaryotic cells, representing a fundamental branch of cellular life, are characterized by a set of distinctive features that distinguish them from eukaryotic cells. These characteristics underscore the elegance and simplicity of prokaryotic organisms, which include bacteria and archaea.

- Lack of Membrane-Bound Organelles: Prokaryotic cells are devoid of membrane-bound organelles such as a nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, or Golgi apparatus. Instead, their genetic material, a single circular DNA molecule, is located in the nucleoid region, a central part of the cell.

- Cell Wall: Prokaryotic cells typically possess a rigid cell wall, which provides structural support and protection. The composition of the cell wall varies between bacteria and archaea, with peptidoglycan being a common component in bacterial cell walls.

- Size: Prokaryotic cells are generally smaller in size compared to eukaryotic cells, typically ranging from 0.5 to 5 micrometers in diameter. This compact size enables efficient nutrient exchange and rapid replication.

- Flagella and Pili: Many prokaryotes are equipped with flagella, whip-like appendages that facilitate motility. Pili, on the other hand, are shorter, hair-like structures that aid in adherence to surfaces and genetic exchange via conjugation.

- Binary fission: Prokaryotic cells reproduce asexually through a process known as binary fission, where one cell divides into two genetically identical daughter cells. This mode of reproduction is highly efficient and contributes to their rapid population growth.

- Plasmids: Prokaryotes often contain small, circular DNA molecules called plasmids, which can carry genes for specific functions such as antibiotic resistance. Plasmids can be transferred between prokaryotic cells, facilitating genetic diversity.

- Metabolic diversity: Prokaryotic cells exhibit diverse metabolic capabilities, allowing them to thrive in a wide range of environments. They can be autotrophic, utilizing inorganic compounds for energy, or heterotrophic, relying on organic substances as energy sources.

- Rapid adaptation: Prokaryotes possess a remarkable capacity for adaptation and evolution, owing to their short generation times and genetic plasticity. This adaptability has contributed to their ubiquity and success in diverse habitats.

In summary, prokaryotic cells are characterized by their simplicity, small size, lack of membrane-bound organelles, and distinctive features such as cell walls, flagella, and plasmids. These traits collectively underscore their efficiency, adaptability, and significance in various ecological niches, making them a cornerstone of life on Earth.

Prokaryotic cell structure

Prokaryotic cells, representing a foundational branch of cellular life encompassing bacteria and archaea, are exemplars of evolutionary efficiency and adaptability. While they may lack the elaborate membrane-bound organelles characteristic of eukaryotic cells, prokaryotes are exceptionally adept at thriving in diverse and often challenging environments, demonstrating the elegance of their minimalist cellular structure.

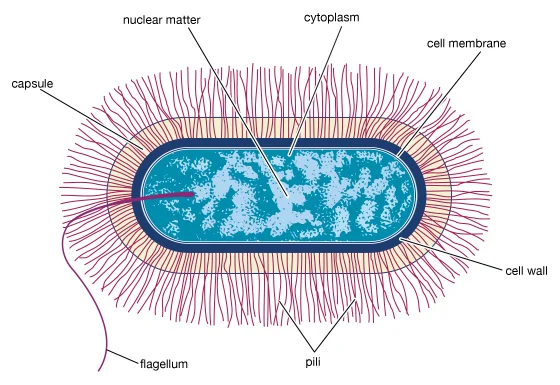

At the core of the prokaryotic cell structure are several key components:

- Cell wall: A robust and protective cell wall encapsulates most prokaryotic cells, working to maintain cell shape and integrity. The composition of this cell wall varies between bacteria and archaea, with the former typically containing peptidoglycan, a unique structural component.

- Cell membrane (Plasma membrane): Surrounding the cytoplasm, the plasma membrane consists of a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins. It serves as a critical interface with the external environment, regulating the passage of molecules in and out of the cell. Beyond its role in transport, the plasma membrane is essential for cellular respiration, energy generation, and various metabolic processes.

- Cytoplasm: This semi-fluid matrix hosts an array of cellular machinery, including enzymes and ribosomes. It serves as the milieu for vital biochemical reactions, making it a central hub for metabolic activities.

- Nucleoid: Unlike eukaryotes with a membrane-bound nucleus, prokaryotic cells feature a nucleoid—a region within the cytoplasm that houses a single, circular DNA molecule. This DNA carries the genetic instructions necessary for the cell’s functions. In addition to the primary chromosome, many prokaryotes harbor smaller, circular DNA fragments called plasmids, which can confer advantageous traits.

- Ribosomes: Prokaryotic ribosomes, known as 70S ribosomes, are the cellular factories responsible for protein synthesis. They interpret the genetic code carried by mRNA and synthesize polypeptides accordingly.

- Pili and Flagella: Some prokaryotic cells possess specialized structures such as pili, which are hair-like appendages used for attachment to surfaces, biofilm formation, and conjugation—a process for the exchange of genetic material. Flagella, on the other hand, are whip-like structures that provide motility, allowing prokaryotes to navigate liquid environments with remarkable agility.

- Capsule: Certain prokaryotes are encased in an outer protective layer called a capsule. This capsule plays a critical role in evading host immune systems, protecting against desiccation, and facilitating attachment to surfaces.

- Plasma membrane extensions: Prokaryotic plasma membranes may exhibit invaginations or infoldings, such as mesosomes in bacteria. The precise function of these structures remains an active area of research, with proposed roles in DNA replication and cell division.

Prokaryotic cells, despite their structural simplicity compared to eukaryotes, are notable for their resilience and adaptability. Their streamlined design facilitates rapid growth, replication, and response to changing environmental conditions, highlighting the profound impact of these microorganisms on Earth’s ecosystems and their critical roles in biotechnology, medicine, and scientific research. Understanding prokaryotic cell structure is foundational for unraveling the intricacies of microbial life and appreciating the versatile solutions that evolution has devised for the challenges of existence.

Reproduction in prokaryote

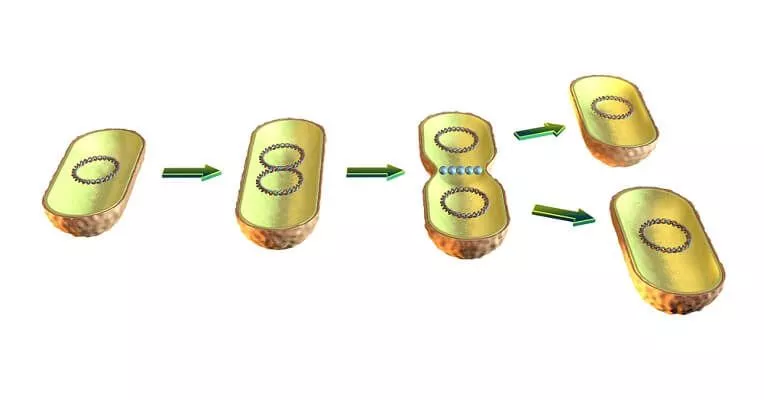

Reproduction in prokaryotes, notably bacteria and archaea, is a fundamental biological process that enables these microorganisms to proliferate and perpetuate their genetic material. This process, known as binary fission, embodies simplicity and efficiency, reflecting the minimalist nature of prokaryotic cells.

Binary fission commences with the duplication of the single, circular DNA molecule present in the prokaryotic cell. This replication initiates at the origin of replication and progresses bidirectionally, resulting in two identical DNA molecules positioned at distinct locations within the cell.

As DNA replication nears completion, the cell elongates and separates the two DNA molecules, a process facilitated by the formation of a septum or division plane across the cell’s midsection. This division plane steadily constricts, ultimately cleaving the cell into two genetically identical daughter cells. Each daughter cell inherits one of the replicated DNA molecules, along with other essential cellular components.

Binary fission is a rapid and efficient means of prokaryotic reproduction, enabling exponential population growth under favorable conditions. Furthermore, prokaryotes can adapt swiftly to changing environments through mechanisms like horizontal gene transfer, including conjugation, transformation, and transduction, which allow for the acquisition of new genetic material.

In summary, reproduction in prokaryotes is predominantly achieved through binary fission, a process characterized by the asexual division of a single cell into two identical daughter cells. This simplicity, coupled with the remarkable adaptability of prokaryotes, underscores their resilience and success in diverse ecological niches, contributing significantly to the Earth’s biodiversity and ecological balance.

Prokaryotic cell vs. Eukaryotic cell

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells represent two fundamental categories of cellular architecture, each displaying a unique set of characteristics that profoundly influence their structure, function, and adaptability. This differentiation underscores a remarkable diversity of life forms and cellular strategies across the biological spectrum.

Prokaryotic cells, exemplified by bacteria and archaea, are distinguished by their relative simplicity. They lack a well-defined nucleus, and instead, their genetic material is housed within a nucleoid—a region within the cell where the singular, circular DNA molecule resides. This genetic material carries the instructions for essential cellular functions. Surrounding the nucleoid is the cytoplasm, a semi-fluid matrix where ribosomes are dispersed, facilitating protein synthesis. Prokaryotic cells also possess a plasma membrane, a protective barrier that regulates the flow of substances in and out of the cell. Furthermore, many prokaryotes feature additional structures such as flagella for movement, pili for adhesion, and a rigid cell wall that provides structural support and protection.

In stark contrast, eukaryotic cells, which form the basis of organisms from fungi and plants to animals, exhibit a higher degree of complexity. One hallmark of eukaryotic cells is the presence of a well-defined nucleus enclosed by a nuclear envelope. This nucleus houses the genetic material in the form of multiple linear chromosomes, protecting it from the cellular environment. Eukaryotic cells also boast an extensive array of membrane-bound organelles, each dedicated to specific cellular functions. Mitochondria, for example, are the powerhouses responsible for energy production, while the endoplasmic reticulum assists in protein synthesis and lipid metabolism. The Golgi apparatus plays a pivotal role in processing and packaging cellular products, and lysosomes serve as cellular waste disposal units.

The presence of these membrane-bound organelles allows for compartmentalization within eukaryotic cells, fostering specialization and cooperation among various cellular processes. Additionally, eukaryotic cells typically possess a dynamic cytoskeleton composed of microtubules, microfilaments, and intermediate filaments, which contribute to cellular shape, motility, and intracellular transport.

In summary, prokaryotic cells exhibit simplicity and streamlined organization, while eukaryotic cells showcase a high degree of complexity and compartmentalization. This dichotomy in cellular structure is not only fascinating but also pivotal in understanding the diverse array of life forms and cellular functions across the biological world. It exemplifies the profound adaptability of life and the remarkable strategies cells have evolved to thrive in their respective environments.

Examples of prokaryotic cell

Prokaryotic cells, renowned for their simplicity and efficiency, represent one of the two primary cell types in the living world, the other being eukaryotic cells. Prokaryotes are chiefly categorized into two domains: Bacteria and Archaea. These microorganisms are characterized by their lack of a true nucleus, which distinguishes them from eukaryotic cells. Here, we delve into notable examples of prokaryotic cells and explore their significance in various biological contexts.

- Escherichia coli (E. coli): E. coli is perhaps one of the most extensively studied prokaryotic organisms. Found in the human gastrointestinal tract, it serves as a paradigmatic model organism for microbiological research. E. coli’s genetic material, a single circular chromosome, resides in a region called the nucleoid, which lacks the membrane-bound nucleus seen in eukaryotic cells. Its simplicity makes it a favored choice for genetic and molecular studies.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Responsible for tuberculosis, one of the world’s major infectious diseases, M. tuberculosis is an exemplar of prokaryotic pathogens. Inside its distinctive cell wall, it contains a nucleoid where genetic material is condensed. Despite being pathogenic and causing significant global health concerns, it adheres to the prokaryotic paradigm with its minimalistic cellular organization.

- Cyanobacteria: Cyanobacteria, often referred to as blue-green algae, are photosynthetic prokaryotes. These ancient microorganisms have played a crucial role in Earth’s history by contributing to the oxygenation of our atmosphere through oxygenic photosynthesis. Their prokaryotic cellular structure contrasts with that of eukaryotic photosynthetic organisms like plants and algae.

- Archaea: Archaea form a distinct domain of single-celled microorganisms. They are known for their ability to thrive in extreme environments, such as hydrothermal vents and acidic hot springs. Methanogens, a subgroup of archaea, produce methane gas during anaerobic digestion, a process vital to various ecosystems and biogeochemical cycles.

- Streptococcus pyogenes: This bacterium is responsible for strep throat and a spectrum of other infections in humans. It presents a classic prokaryotic cellular structure, with a nucleoid region housing its genetic material. Understanding its prokaryotic biology is crucial in devising treatments and interventions for streptococcal infections.

- Salmonella: Salmonella species, including Salmonella enterica, are notorious for causing foodborne illnesses. They serve as prime examples of prokaryotic pathogens. Their compact and efficient cellular organization enables them to persist in diverse environments and colonize hosts efficiently.

- Prochlorococcus: These minuscule photosynthetic prokaryotes inhabit the world’s oceans, playing an essential role in marine ecosystems. They possess a single circular chromosome and a streamlined cellular structure, underscoring the elegance of prokaryotic simplicity in ecological niches.

These diverse examples highlight the ubiquity and importance of prokaryotic cells in nature. Their fundamental cellular organization, characterized by the absence of a membrane-bound nucleus and complex organelles, makes them intriguing subjects of study. Prokaryotic cells exemplify nature’s capacity to adapt, survive, and thrive in an array of environments, from the human body to extreme ecological niches. Their minimalistic yet efficient cellular design continues to be a source of fascination and scientific exploration.

Prokaryotic cells, with their elegance in simplicity, form the foundation of life on our planet. Their unassuming nature belies their profound impact on the biosphere. As we peer through the microscope into the realm of prokaryotic life, we uncover the essential elements of cellular existence. From the humble beginnings of the first cells to the astonishing diversity of modern bacteria and archaea, prokaryotes continue to shape the course of life’s journey on Earth, reminding us that simplicity can be the cornerstone of complexity.

Resources

- BOOK Madigan, M. T., Bender, K. S., Buckley, D. H., Sattley, W. M., & Stahl, D. A. (2018). Brock biology of microorganisms. Pearson Higher Education.

- BOOK Alberts, B., Johnson, A., Lewis, J., Morgan, D., Raff, M., Roberts, K., & Walter, P. (2014). Molecular biology of the cell. Garland Science.

- BOOK Tortora, G. J., Funke, B. R., & Case, C. L. (2013b). Microbiology: An Introduction. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company.

- JOURNAL Woese, C. R., & Fox, G. E. (1977). Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: The primary kingdoms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 74(11), 5088–5090. [PNAS]

- JOURNAL Whitman, W. B., Coleman, D. C., & Wiebe, W. J. (1998). Prokaryotes: The unseen majority. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95(12), 6578–6583. [PNAS]